ARCHIVE

The Translated Man:

Matvei Yankelevich on Daniil Kharms: An online exclusive interview

An online exclusive interview

Friday, December 21, 2007

By Michael Helke

From “Blue Notebook #10,” written by Daniil Kharms, translated by Matvei Yankelevich:

“There was a redheaded man who had no eyes or ears. He didn’t have hair either, so he was called a redhead arbitrarily. He couldn’t talk because he had no mouth. He didn’t have a nose either. He didn’t even have arms or legs. He had no stomach, he had no back, no spine, and he didn’t have any insides at all. There was nothing! So, we don’t even know who we’re talking about.” The final line: “We’d better not talk about him any more.”

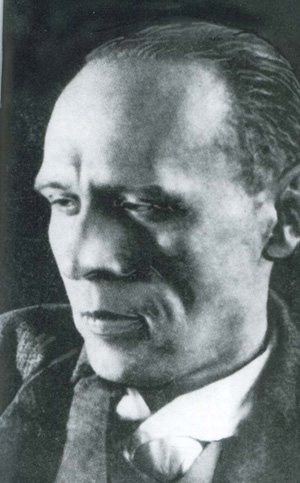

Born Daniil Ivanovich Yuvachev in St. Petersburg, in 1905, he came up with his surname while still in high school. (“Kharms” is pronounced with a hard “H,” much like how you’d pronounce “Hanukkah” if you were Jewish.*) Kharms became best known for his poems and stories for children — which was doubly odd, because he professed an abhorrence of children, and because he wrote them for as long as he did (1928 to 1941). Then there are the works, like the above-quoted “Blue Notebook,” that were a truer distillation of Kharms’s worldview and, as a consequence of the period and place in which he lived, would never be published in his lifetime. Critics whose habit it is to read a writer’s autobiography in a writer’s work tend to look to those years and that place — Russia under Joseph Stalin, when people disappeared without explanation, as if, like the redheaded man, they had never even existed — for an explanation of that final line.

While they wouldn’t be entirely wrong in this generalization (stopped clocks and such), the effect of accepting it as holy writ subjects the work to the redheaded man’s fate: of being erased at the very moment of creation. In Kharms’s world, shit happens for no discernible reason; the notion of an agency for shit’s happenstance is negligible. No cause, therefore no effect. No Stalin, no Soviet Union, no Black Mariah. A father and a daughter keep dying, getting buried, and coming back, while their neighbors step out to the cinema and disappear for good. Kuznetsov passes a construction site and keeps getting beaned, Krazy Kat-like, by falling bricks. With each brick, Kuznetsov loses cognition in increments, until at last he forgets everything he ever knew and goes running down the street crying “Uga-gu.” Koratygin and Tikakeyev are spied bickering over a trivial matter; the scene degenerates into an exchange of insults, and culminates in Tikakeyev banging Koratygin over the head with a cucumber. Koratygin falls over and dies. The narrator who observed this scene sums it up thusly: “What big cucumbers they sell in stores nowadays!” The revered Russian poet Alexandr Pushkin meets the revered Russian novelist Nikolai Gogol onstage, and the outcome of this meeting of the minds is an endless loop of the two tripping and falling over each other; neither has anything memorable to say on the occasion, alas. The landscape these characters inhabit is impoverished and brutal, to be sure, but, contrary to the decrees of dialectical materialism, their individual fates are hardly a result of this. Shit, as it happens, happens.

In the so-called real world, Kharms’s failure to make good with dialectical materialism and its aesthetic offshoot, Socialist Realism, had a great deal to do with how his life and work played out. As the founder of the avant-garde collective OBERIU, or Union of Real Art, Kharms propounded the separation of art from the dictates of logic and tradition, as if he wanted an aesthetic that might achieve escape velocity and set off for new worlds to conquer. Toward that end, he staged nonlinear, anti-rational theatrical works; wrote like-minded poems, stories, and “scenes,” most only a few paragraphs in length, and many devoted to the synergy created when sound and sense don’t harmonize with so much as smack into each other; and, as discussed later in this interview, endeavored to make his very physical person a model for this new mode of perception. As a consequence, colleagues found him to be a very strange man.

By the time Stalin consolidated his power in the early thirties, such avant-garde expressions were deemed subversive, dangerous to the practical aims of the state (work, work, and more work). People — friends, collaborators — began to disappear. Kharms himself fell under suspicion, particularly for his children’s writings, which were judged anti-Soviet (in its refusal to instill Soviet values, i.e. work, work, et al). In 1931, he was arrested and exiled to Kursk. As his sole means of income, Kharms continued his children’s works, though he had to keep a lower profile, the pay wasn’t as good as before, and his editors were increasingly squeamish in the face of state intervention. With the OBERIU disbanded, opportunities for staging new works dried up. Hungry and up to his eyeballs in dept, with his creative life effectively placed under surveillance, Kharms lived a secret life, keeping his more adventurous works hidden from scrutiny, save for that of family and select friends. He was arrested for the final time in 1941, on suspicion of treason. When interviewed by the police as to the nature of his activities, he told them; and was summarily remanded to the psychiatric ward of Leningrad Prison No. 1. By then, Germany had invaded Russia and placed Leningrad under siege. Food became scarce. The city was turning into one big potter’s field. Kharms was found dead in his cell in February 1942, most likely from starvation.

As the blockade dragged on, Yakov Druskin kept his friend’s manuscripts out of danger, lugging them around in a suitcase. Had he not done so, it’s possible that Kharms would be remembered only through his children’s writings. In the 1960s, Kharms’s work circulated samizdat-style among the era’s intelligentsia. (Although they didn’t have Stalin to worry about by then, they had Krushchev and then Brezhnev, which was enough, so they kept their activities quiet.) They had opened the suitcase and liked what they saw. Word spread. A complete collection of his works was later published in four volumes between 1978 and 1988. Kharms’s posthumous influence grew, and keeps on growing.