ARCHIVE

A More Bukowskian Chinaski: Factotum: The Stop Smiling Film Review

The Stop Smiling Film Review

Friday, August 25, 2006

Factotum

Directed by Bent Hamer

In theaters now

Reviewed by Josh Tyson

American poet and novelist Charles Bukowski once called Hollywood a hemorrhoid on the asshole of art. This probably had something to do with his experiences during the production of Barbet Schroeder’s Barfly (1987), for which he wrote the screenplay. Among other things, Bukowski took issue with Mickey Rourke’s portrayal of Henry Chinaski — the author’s steadfast alter ego — calling it too loud and flamboyant. It’s true, Rourke does lay it on thick. But Barfly is easily one of the best films of the ’80s, and Rourke’s performance is largely to credit.

Were he alive to see it, Bukowski might be more appreciative of Matt Dillon’s take on Chinaski in Factotum, the new film by Norwegian director Bent Hamer. The events in the film occasionally stray from the source material — a novel of the same name in which a young Chinaski bounces around the country working one shitty job after another — and branch out to include some of Bukowski’s other writing, but Dillon’s performance is doggedly loyal. Like Rourke, Dillon staggers through his days in soiled clothing, walking as though he’s got wet shit in his shorts — or perhaps a tinselly hemorrhoid — but he forges a much quieter presence. A third of Barfly’s runtime is devoted to Rourke drinking at an LA dive called The Golden Horn and getting into sloppy brawls with one of the bartenders. In Factotum, Dillon spends more time alone, writing and drinking in cheap rooms and sending weekly batches of stories to literary magazines.

We first see him wearing a parka, looking sickly and miserable, jackhammering at a slab of ice. His boss tells him to put the drill down and help make some deliveries. Fortunately for Chinaski, the first stop is a bar. A short while later, his boss pulls up in an orange PT Cruiser, to find all the ice in the truck melted and Chinaski drinking inside. He is promptly fired, the first of many terminations.

The orange PT Cruiser and the parka are noteworthy because they give evidence early on that Chinaski has been yanked from his native Los Angeles — the film was shot in Minneapolis — and is living in the present. In the novel, Chinaski wanders an America in the depths of World War II, taking buses from coast to coast and eventually crash-landing in LA. Deemed psychologically unfit for military service, he finds constant reminders of his square-peg ways in his inability to find work and/or women while so many men are overseas and the odds are in his favor.

The fact that Chinaski can be ably transplanted from the ’40s to the early 21st century, and from LA to MN, speaks to his endurance as American literature’s preeminent antihero, and Dillon seems to have a firm grip on this notion. He gives a restrained and thoughtful interpretation, such that even voice-over narrations explaining his approach to writing don’t come across as obnoxious. As he lies in bed drinking a cheap pint and staring at the ceiling, you can see the great mind of a craggy poet churning behind his weary eyes. His splotchy red face and scummy beard hang like faded war paint. Dillon’s is a Chinaski that will always be out of time and place — especially in a culture where, now more than ever, work and earnings are pillars of “successful” living.

“Frankly I was horrified by life,” Bukowski writes in the novel, “at what a man had to do simply in order to eat, sleep, and keep himself clothed. So I stayed in bed and drank.” Dillon finds the same soul-sucking grind in a bicycle-parts warehouse, a pickle factory, the custodial department of a newspaper and a brake manufacturing plant. The jobs are short-lived and don‘t end well, but he presses on with a regal strain of reluctance. As he defiantly explains to one boss after being fired, “I’ve given you my time. It’s all I have to give — it’s all any man has.”

The only source of income he finds at all worth devoting himself to is betting on horses. The desperation at the tracks is right out in the open, and for Chinaski, losing money on horses is better than losing dignity and time behind the punch clock.

Much of Chinaski’s time is also sucked up by women, and no Bukowski tale is complete without at least a few equally errant females to share a rented room and a jug of port. The first of these is Jan (Lili Taylor), who seems to hate work as much as Henry does. They spend much of their time holed up in filthy rooms, humping on their soiled sheets, drinking rotgut and eating pancakes cooked in a dry pan. Taylor seems sculpted for the part, looking haggard and lusty at the same time and carrying the character with the perfect balance of vulnerability and craze.

In between trysts with Jan, he falls in with Laura (Marisa Tomei), who leads him on an darkly serene tangent involving her wealthy benefactor and two of his other mistresses. There’s actually a scene from Barfly that repeats itself here, where Laura (Wanda in Barfly, aced by Faye Dunaway) buys the pair a night’s supply of booze and a cigar on her old man’s credit. They head back to her apartment and, as Rourke did in Barfly, Dillon waxes on the eternal magnificence of a woman’s legs.

The funny thing about Bukowski’s distaste for Rourke’s performance is that he wrote the script. So at least some of the bravado that Rourke effuses came straight from the page. Not caring much for Hollywood to begin with, it’s not surprising that Bukowski wouldn’t enjoy a big screen caricature of his own creation. Dillon has the advantage of working from material not designed for the screen, and the character is more three-dimensional because of it. Rourke’s Chinaski was more about Bukowski the mythic beast; Dillon’s is about Bukowski the listless human.

Put stupidly, Dillon is more the waltzing grizzly to Rourke’s panda on a unicycle. He drinks. He writes. He works. He waits.

In a passage from the book that makes its way into the film, Dillon ruminates that anytime he gets discouraged about writing, he need only pick up a book and read a little. In no time he’s reminded that he can do better.

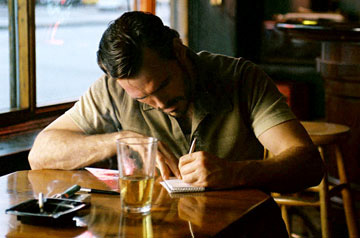

Dillon says it in a voice-over, while sitting in a bar scratching notes in a pocket-sized notebook. His dedication to his craft is a subtle reminder that, in an age where popular literature is fast becoming a hemorrhoid all its own, anyone can do better if they mean it.