ARCHIVE

Spalding Gray: The Last Digression

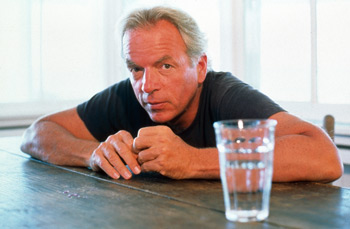

Spalding Gray / Photograph by Scott Schulman

Wednesday, January 10, 2007

By Steve Finbow

A car is driving along a dark Irish country road on July 22, 2001. Its occupants, who are returning from dinner, are Tara Newman, Timothy Leary?s widow Barbara, her boyfriend Kim Esteve, and Spalding Gray and his wife, Katherine Russo. Kathie, as she?s known, sits behind the wheel; she has been chosen because she has not had as much to drink as the others. Spalding sits in the backseat, unbuckled.

And this is where the world goes Gray. At a notorious ?black spot? on the road, the car collides head-on with a van driven by a local veterinarian delivering mad-cow disease vaccine to the local farms. The crash spins the car three times. The impact thrusts the engine through to the driver?s seat. Everyone is injured ? Spalding the most seriously.

What happens over the next few weeks can only happen to Spalding and, as it happens, it changes him irrevocably. Having to endure Irish hospitals full of drunken farmers, inept Pakistani doctors, cross-dressing nurses, antique spinal braces, bereft of state-of-the-art medical equipment ? surely this is fuel for Spalding Gray?s cool ironic fire?

Written in the months after the accident, performed throughout 2002 and 2003 as an introduction to Interviewing the Audience and a revised version of Swimming to Cambodia, Life Interrupted shows Spalding spiralling down into depression. No more the perpetual na?f staring wide-eyed at the illimitable absurdity of the world, the author of Life Interrupted is bitter in his humour, revengeful in his bafflement, narrow-eyed in his vindictiveness. Spalding?s not waving, man, he?s drowning.

Three years ago, on the evening of January 10, 2004, Spalding Gray, after checking in with his children by phone, leapt from the Staten Island Ferry. A body was pulled from the East River two months later. Dental tests and X-rays confirmed that the body was that of the author of Swimming to Cambodia.

For 30 months, Spalding had lived in a Bardo Thodol of the body and mind. For a man used to travel, skiing, and acting, having to learn to walk again incapacitated his spirit. For a man so lithe of brain, nimble of word, swift of thought, the right-frontal-lobe damage he suffered caused a debilitating depression that could not be eased by his usual humour, bravery, and perspicacity.

The townspeople of Sag Harbor, the town in which Spalding Gray lived with Kathie, their sons Theo and Forrest, and Marissa, Kathie?s daughter from a previous marriage, had seen Spalding attempt suicide on a number of occasions: usually, he had to be talked down from the local bridge. Sag Harbor was long his refuge; it was where the domestic fears and delights of Morning, Noon, and Night ? Gray?s monologue on how people live as a family ? had its origin. It was after the completion of this paean to contentment that Spalding feared he would never write another monologue ? what could he write about? Life was almost perfect. The targets of Spalding?s comically metaphysical gaze had receded from view. Spalding?s Magoo-like unawareness of adversity in the face of happiness seemed to be destroying his art ? and then along came Ireland. But what came before?

Spalding Gray?s masterpiece Swimming to Cambodia is a near-perfect monologue on the subject of? of what? According to the back-cover blurbs, it details his time working as an actor in Roland Joff? and Bruce Robinson?s The Killing Fields. But acting was only a base camp for further investigations. Reading Swimming to Cambodia is reading prose plus voice plus timing plus rhythm. Paragraphs act as pools from which issue digressive tributaries, which in turn lead to invasive streams of consciousness, vortical memoirs, and still further autobiographical divagations. No cheap reminiscences and throwaway memories, the discursive prose take us away from the entrapments of ego, moves us through sensitized examinations of contemporary life, and reveals to us the many reasons we tell stories But Spalding never rambles. This no Kerouacean ?first thought, best thought?, but rather seamless digression ? structured, almost poetic in scope. Imagine a voice fusing/bluesing the cool authorial dialogue of Elmore Leonard with the mediatized American idiom of William Carlos Williams. Imagine that voice, and internalize it.

That voice. Huck Finn used it. Holden Caulfield appropriated it. But whereas Holden would pretend he was a deaf-mute in order not ?to have to have any goddamn stupid conversations with anybody?, Spalding Gray, particularly in the shows that made up Interviewing the Audience, used other people?s autobiographies as catalysts for his own stories ? he shared our stories with us. Nothing for Spalding was ?phoney?. Before the accident, everything was new, shiny, and appropriable. Spalding?s magpie mind made kaleidoscopic the nest of his narrative. The voice ? New England ? calms the bubbling dread we all feel. Exuberantly vicarious, the monologues soothe our anxieties with a balm of modesty and self-accountability.

Spalding on stage: he sits behind a table, a microphone, a spiral notebook from which he will depart and return, from which he will cull and collect. Dressed in a plaid shirt, his hair grey, he sips from a glass of water. Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, David Antin and Garrison Keillor could also be on that stage, except? except? Allen wouldn?t be able to keep still, Bill would be as funny but cold and sardonic, David as parenthetical yet more serious, Garrison comfortably at home selling us a Honda. Spalding Gray looks up and we know he?s going to nail it ? whatever the subject. He tackles adolescence in Sex and Death at the Age of 14; his career and other demons in Swimming to Cambodia; his problems with the novel in Monster in a Box; his health in Gray?s Anatomy; love, skiing, and fatherhood in It?s a Slippery Slope; domesticity in Morning, Noon, and Night; and the impossibility of creativity in the face of death in Life Interrupted. Throughout the seven major monologues, he is forever writing around his mother?s suicide, circling it, knowing it intimately, respectful of its power, weighing its heft, its authenticity. Detail: it?s all in the detail. Fear: it?s all in the fear(lessness).

Spalding?s ?to be? was always part of his ?not to be?. Death ? accompanied by hypochondria and doubt ? haunted him. Impossible Vacation, his only novel, is a fictional reconstruction of his life events, his childhood, his travels, his affairs; yet it somehow disappoints, as if the roman ? clef form detracts from the voice we hear in our heads ? it?s Spalding but not as we know him. Spalding?s voice, in the published monologues ? and in any of the recorded performances ? is one we trust: one of candour, simplicity. It presents us with neuroses and paranoia; it draws attention to itself, but only in its revelations.

?I tell him it is for an eye problem. Oh, he assures me that he is very good with eyes. In fact he?s been known to pull an eye right out of the skull, lift it up, display it, wash it off, and put it back in the person?s eye socket.

?I said, ?How do you reconnect the veins after that? How do they all get hitched up?'

?He said, ?We don?t know. This is a mystery.?

?I can?t believe this is going on. I go back to my hotel, and I get very little sleep that night.?

?We know. We know,? we keep saying. ?Thank god, it?s not happening to us.? Spalding?s humour is far more Freudian than Bergsonian ? he wanted to outwit the censor, to go beyond inhibition, to investigate impulsiveness, and to extemporize morality. Unfortunately, the censor was usually Spalding.

In the three years since Spalding?s death, it?s as if everyone?s at it ? the memoir, the autobiography, the monologue. David Sedaris, Augusten Burroughs, Neal Pollack and Jonathan Ames have all plunged into the choppy waters of the confessional ? the Tellus Straits. But only Spalding Gray could serve up that admixture of humour, tragedy, naivety, and relentlessness. And it is only Spalding Gray among these self-confessors of American letters who may be considered sui generis.

On the afternoon of the day he disappeared, he took his children to see Tim Burton?s Big Fish. On leaving the cinema, Spalding was in tears. In the movie, a dying father, after having spent his life telling tall tales, transforms into a catfish and swims off into the other world. Somewhere in my imagination, Spalding Gray, alone on the closed deck, hauls himself painfully over the rails of the Staten Island Ferry, no longer suffering from hurt in mind and limb, preparing to escape his demons and set off on the longest swim.

Steve Finbow, a London expat who contributes his observations on life in Japan for Seppuku My Heart, and a recent finalist for the the 2007 Willsden Herald short story prize, had his own near-death experience fairly recently, over the Christmas holidays. Having gone into a diabetic coma on 19 December, he snapped out of it on Boxing Day to the sight of a collection of Japanese doctors and nurses plying him with Christmas carols. Soon he will be off to Johannesburg on a temporary teaching jag. We wish him well and advise him to avoid fields of sugar cane.